We understand that some of our customers may be affected by the Canada Post service disruption where mail delivery could be delayed. Take steps now to ensure continued access to your Hydro Ottawa bill and account information online. Learn more

RPP electricity prices, winter hours and thresholds, and the Ontario Energy Rebate changes take effect Nov. 1, 2024.

Visit our revamped Outage Centre for helpful tools and resources, like our new outage map and outage alerts.

Hydro Ottawa''s 2023 Scorecard is now available. Gain insight on how Hydro Ottawa is performing.

2711 Hunt Club Road,PO Box 8700Ottawa, ON K1G 3S4

Ontario''s electricity market is materially different than the one envisioned when it opened in May 2002. In the lead-up to market opening, the electricity market was expected to provide competition, lower prices and transparent price signals to both consumers and investors.

Yet, over time, those principles became secondary concerns, overridden by new priorities that increased prices, reduced competition and distorted price signals.

Ontario again redesigning its key components of its electricity market in an effort to make good on a number of the promises made in 2002. This report provides a guideline to both what went wrong and whether these issues will be addressed going forward.

PART I: THE RISE AND FALL OF PUBLIC POWER IN ONTARIO

The story of Ontario''s electricity market really begins in 1906.

It was then that the Hydro Electric Company of Ontario (HELCO) — or "Hydro" — was founded by the province and led by Adam Beck. While Hydro was established to build, own and operate a transmission network to deliver power across Ontario, it quickly broadened this vision to include the construction of hydroelectric dams.[1] The mantra of Hydro was to deliver, "power at cost."[2]

Hydro eventually came to take over the entire electricity sector, but not without controversy. By the 1920s, after a series of cost overruns at one of its largest generation projects — the Queenston-Chippawa Generating Station (later renamed Adam Beck 1) — Hydro''s debt accounted for more than one-half of the province''s total debt.[3] One commission in 1924 found that many of Hydro''s construction projects were unjustifiably elaborate and costly.[4]

But with Hydro''s importance to the growing electricity sector and the provincial economy firmly established — as well as remaining popular with the public at large — Hydro''s economic and political influence grew stronger.

Demand for power continued to grow year-over-year and decade-over-decade, leading Hydro— officially transformed into a crown corporation in the 1970s and renamed Ontario Hydro — to expand its generation fleet beyond hydro dams. In the 1950s and 1960s it began construction on a series of large coal generators, such as the Lakeview generating station — the largest coal plant in the world at the time.[5]

By the 1970s, Ontario Hydro began construction on a series of nuclear generators, bringing the four-unit Pickering Generating Station into service in 1971, the first large-scale nuclear plant in Canada. In the 1970s and 1980s, Hydro built the four-unit Bruce Generation Station (Bruce A), four more units at Pickering (Pickering B) and another four units at Bruce (Bruce B). In 1990 — after years of delays and billions of dollars in cost overruns — Ontario Hydro completed the four-unit Darlington Generating Station, fully transforming itself into a predominately nuclear utility.[6] By 1992, its nuclear fleet accounted for 53 per cent of total output.[7]

Ontario Hydro''s nuclear ambitions stood in stark contrast to its financial health. When the Darlington plant was completed in 1991, Ontario was suffering from a severe economic recession, yet Ontario Hydro was pushing for a 40 per cent rate increase.

At the time, Ontario Hydro''s debt amounted to more than one third of the province''s total indebtedness. The financial deterioration culminated in a series of write-downs. First, a $3.6 billion write down in 1993 and later a $6.6 billion write down in 1997.[8] These were the two largest write downs in Canadian corporate history. In 1993, the province implemented a rate freeze that was to remain in effect for the remainder of the decade and into 2002.[9] By the end of the 1997, eight of Ontario Hydro''s 19 nuclear reactors were shut down due to poor performance and safety issues.[10]

Ontario Hydro''s reputation, like its finances, was teetering on the brink of collapse.[11]

One of the biggest problems facing Ontario Hydro was that it overbuilt the grid on the assumption that electricity demand would continue to grow, as had occurred throughout the 20th century. In the late 1980s, Ontario Hydro forecast demand would hit 184 TWh by 2000 — nearly 20 per cent higher than actual demand of 153 TWh in that year and more than 50 TWh higher than demand in 2017.[12] In the short-term, Ontario Hydro expected demand to reach 159 TWh in 1994, even though actual demand turned out to be 135 TWh.[13]

In short, the utility had too much supply and too little demand.

Given that many of Ontario Hydro''s costs were fixed, lower demand increased the average cost to be recovered for each unit of power generated. The result was Ontario Hydro asking for a 40 per cent rate hike in the midst of a recession. A public reckoning on the fate of public power took hold.[14]

By 1999, Ontario Hydro''s reign as the province''s electricity monopoly was officially over.

In the end, Ontario Hydro was left holding $38.1 billion in debt and other liabilities, with more than half of that amount — $20.9 billion — unsupported by the value of its assets. Ultimately, $7.8 billion of that debt was unable to be paid down from future revenues and was collected from ratepayers in the form of a monthly charge known as the Debt Retirement Charge, which remained in effect until April 2018.[15]

Ontario Hydro''s financial demise shook the provincial legislature and economy. It also coincided with a push in the 1990s — both in Ontario and jurisdictions around the world — to deregulate the energy sector and transition to one based on competition and market principles, rather than a government-owned, top-down public utility model.[16]

In 1995, an Advisory Committee — known as the Macdonald Committee — was established to "study and assess options for phasing in competition in Ontario''s electricity system." The committee called for an end to Ontario Hydro''s monopoly on generation, an independent transmission network open to private generators, an independent system operator and a new regulatory structure to oversee the sector and allow for greater independent oversight. It also called for full retail and wholesale competition. The report was a stark break with the last century of Ontario Hydro''s dominance.

The committee''s recommendations paved the way for the eventual breakup of Ontario Hydro in 1999 into five parts — Ontario Power Generation (OPG), Hydro One, the Independent Market Operator (later renamed the Independent Electricity System Operator), the Electrical Safety Authority (ESA) and the Ontario Electricity Financial Corporation (OEFC). One key recommendation was that Ontario Hydro''s generation division be split into various units and required to compete against one another. The report called for the nuclear unit to be split into competing entities, the hydroelectric stations to be grouped by river system and the thermal units to operate as distinct entities.

By 1997, the Government of Ontario issued a white paper laying out its vision for the electricity sector — stopping short of adopting the full list of recommendations from the Macdonald Committee. While the white paper called for splitting Ontario Hydro into a generation business and a transmission and distribution business, the generation business — comprising of nuclear, hydroelectric and thermal generators — would remain under public ownership and control nearly the entire market.

By 1998, the Government of Ontario passed Bill 35, the Energy Competition Act — which included the Electricity Act and the Ontario Energy Board Act — that formally laid out the breakup of Ontario Hydro. It also provided the Ontario Energy Board greater power in setting rates, among other changes.

The end of Ontario Hydro was complete.

The underlying theme in both the Macdonald Committee and the subsequent white paper was that a "competitive" electricity system would overwhelmingly benefit the province and its ratepayers by reducing prices. The push for deregulation was supported by a number of key industry players, notably the Association of Major Power Consumers in Ontario (AMPCO) and Independent Power Producers'' Society of Ontario (IPPSO).[17] Small volume customers (largely households) appeared eager to participate in the competitive retail market, with nearly one million of Ontario''s more than four million electricity customers having signed contracts with various retail intermediaries by the time the market opened in 2002.

While the market was initially scheduled to open in 2000, that date was subsequently pushed back to May 2002.

The MPMA contained two key proposals. First, it capped the price paid to OPG on 90 per cent of its domestic sales at 3.8 cents per kWh. Anything above that amount — if wholesale prices were greater than 3.8 cents per kWh — would be rebated to Ontario consumers. Secondly, within ten years of the market opening, OPG would reduce its generating capacity to no more than 35 per cent of Ontario''s total capacity. OPG would also reduce its control of price setting, or marginal, generating plants to 35 per cent of the province''s total within 42 months.

In July 2000, OPG agreed to an 18-year lease with a private consortium to operate its four Bruce B nuclear units. OPG hailed the lease as "a major initial step" in meeting the terms of the MPMA.[18] In 2002, OPG also sold four hydroelectric generators with a total capacity of 490 MW.[19]

Yet, contrary to the MPMA, OPG''s market power was never reduced to the levels imagined prior to market opening. In 1999, for example, OPG moved forward with its decision to bring the four Pickering A units back into service. By 2012 — ten years after the market opened — OPG''s in-service generation capacity remained at 53 per cent.[20] In 2005, it still owned as much as 72 per cent of installed capacity in Ontario.[21] OPG continues to own and operate around 50 per cent of installed capacity.

PART III: ONTARIO PULLS BACK FROM DEREGULATION

About Ottawa electricity market

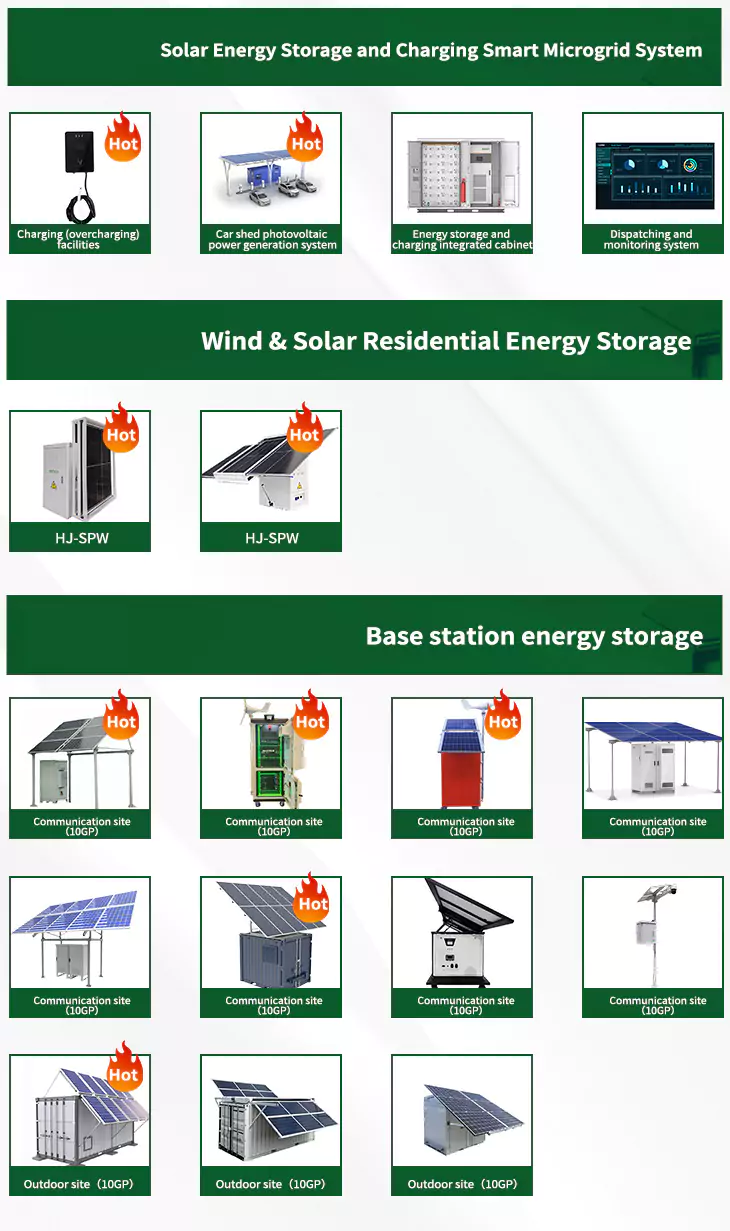

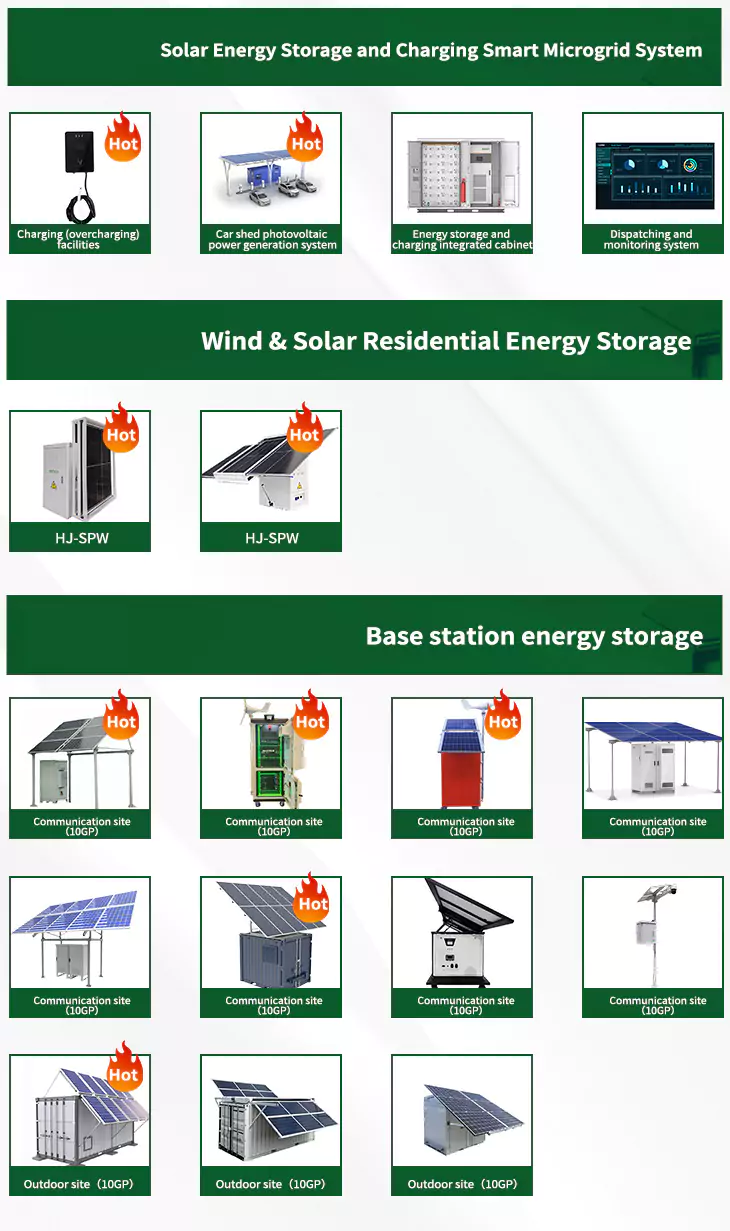

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in Ottawa electricity market have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient Ottawa electricity market for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various Ottawa electricity market featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents