Crossway Road, Port Area, PO Box 493, Betio K10108, Tarawa – Republic of Kiribati

Kiribati Green Energy Solution, a State-Owned Enterprise was established on 14 November 1984 under the Company Ordinance Cap 10A. It is a leading Government implementing agency in the energy sector deal with any renewable energy initiatives in Kiribati.

The Company aim to establish itself in leading Kiribati as the most trusted partner in providing green energy solutions as set out in its Mandates. In 2020, the reformation and renaming of the Company (commonly known then as Kiribati Solar Energy Company) was conducted with the core objective is to broaden its scope in providing services with renewable energy including solar energy, wave energy, wind energy and other RE technologies that is applicable in Kiribati.

The Kiribati Green Energy Solution headquarter office building is located in Betio, Tarawa Island. The Company currently have 3 branch office buildings located in London Kiritimati Island, Tebikerai Maiana Island and Nuotaea Abaiang Island. The Company also have outlet retail store located in Bonriki International Airport, Tarawa. There is a development plan for the Company''s branch office buildings to be established and reached all outer islands with the ongoing rural electrification project.

Kiribati Green Energy Solution, a State-Owned Enterprise was established on 14 November 1984 under the Company Ordinance Cap 10A. It is a leading Government implementing agency in the energy sector deal with any renewable energy initiatives in Kiribati. Read more …

PROMOTING OUTER ISLAND DEVELOPMENT THROUGH THE INTEGRATED ENERGY ROADMAP (POIDIER) PROJECT

Promoting Outer Islands Development Through the Integrated Energy Roadmap (POIDIER) project is a climate mitigation project funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) trust fund. The project is implemented by UNDP in partnership with the Government of Kiribati.

The main objective is to enhance the outer island development through the achievement of renewable energy (RE) and energy efficiency (EE) targets of Kiribati as stated in the Kiribati Integrated Energy Roadmap (KIER). The project was launched in January 2021 and is anticipated to complete in 2024.

The demo PV mini-grid systems will be installed on the outer islands/rural areas and it will be the first to have a revenue and billing system to facilitate financial sustainability. High-quality solar grid systems at globally competitive costs will be installed and distributed to the outer islands.

POIDIER also relates its mission to support the Kiribati Development Plan (KDP) – (2016-2019) to advance inclusive economic development in the following areas:

For further information and updates on the project activities and progress. Please visit POIDIER Facebook Page here.

BUARIKI, KIRIBATI — As late as 1990, nightfall in Kiribati (pronounced "Kiribass"), a patchwork of tiny islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, was accompanied by a peculiar odor. More than 60 per cent of the country''s 103,000 people had no electricity, and whenever dusk fell, many of them would light greasy kerosene lamps in order to see.

The kerosene fumes were unavoidable, villagers recalled, and the light was not quite suitable for weaving or reef fishing — two economic activities that are central to village livelihoods. "Uncomfortable and annoying," recalled Roniti Piripi, a villager on North Tarawa, a two-hour boat ride from the grid-connected capital in South Tarawa.

But in 1991, an agent from a government company came to his village, Buariki, and offered to lease him a solar home system for a one-time payment of US$52 and regular monthly payments of $7. Piripi said he leapt at the opportunity and hasn''t looked back. The solar system that he leased 25 years ago now powers his family''s home and dry-goods shop on Buariki''s unpaved main street. They also have a second solar panel from the energy company, which they purchased for around $170, and several hand-held solar lights (donated to 10,000 Kiribati households last year by the Taiwanese government).

"Once we got solar energy, everything was easy," Piripi''s wife, Taanti Kaitangare, recalled as she sat in a thatch-roofed, open-air meeting space, known as a maneaba. "We''re so much happier."

Since 1991, the state-owned Kiribati Solar Energy Company (KSEC) has distributed approximately 4,400 home solar systems across 21 of the country''s 33 islands and received millions of dollars in development assistance from Japan and then the European Union, according to Tavita Airam, the company''s chief executive.

Villagers in off-grid areas are "really happy because women can do the weaving, and men can go out fishing, using the lights," he said recently in his office, a squat residential building in South Tarawa, near the country''s only industrial seaport.

But the 25-year solar rollout in Kiribati hasn''t always gone smoothly, according to officials and energy consultants. Airam also concedes that KSEC''s US$75,000 maintenance fund for its solar equipment is underfunded by half, and that with EU assistance scheduled to formally end in March, the company''s long-term growth strategy will depend on the government''s willingness to subsidize it.

Kiribati''s energy story highlights both the successes and pitfalls of off-grid solar projects in the South Pacific, a region that includes some of the world''s poorest countries. On one hand, energy experts say such initiatives have brought power to thousands of remote villages despite enormous geographic and logistical obstacles. But they add that the region''s solar programs, which are typically funded by international donors, have been plagued by bureaucratic inefficiency and a chronic lack of attention to long-term economic and technical sustainability.

“Systems are installed, and then what? The batteries fail, and after five or six years people want to replace them — but no one has money set aside.”Peter Konings, chief executive of Asia-Pacific Energy GroupA typical South Pacific scenario goes something like this: A solar program gets off to a bright, promising start, but burns out after millions in donor funding have been spent. National utilities eventually lose interest in providing solar systems, while technicians lack technical capacity to fix them. The poorest and most isolated villagers can''t afford to buy them or pay for repairs. The systems deteriorate until another set of donors comes to the rescue — at least for the time being.

"Systems are installed, and then what? The batteries fail, and after five or six years people want to replace them — but no one has money set aside," said Peter Konings, chief executive of Asia-Pacific Energy Group, an American energy company that operates across Asia, Europe and Africa and specializes in off-grid solar development.

"You want to do a good job, but basically you''re putting solar systems in places where there''s no cash economy," he continued. "There''s no monthly income, so how can they make monthly payments?"

Kiribati''s 33 islands are spread across 3.5 million square kilometres of ocean, but the total land mass is about half the size of greater London. The two-hour boat ride across an ocean lagoon from South to North Tarawa is short by local standards; Airam said it can take nearly two weeks to ship KSEC solar equipment from South Tarawa''s port to some of Kiribati''s more remote islands. (He usually flies to site visits.)

The Pacific Ocean has some of the world''s most productive fishing grounds, and fish is a key source of food security in Kiribati and neighbouring countries. Yet the ocean''s vastness also impedes economic development. Pacific Island states are "unique in their remoteness," even among other small-island developing states, the World Bank reports. Oceania, as the wider region is sometimes called, covers an area roughly the size of the contiguous United States. But its total population, including Australia''s and New Zealand''s, is about 38 million — roughly equivalent to metropolitan Tokyo.

The vast swaths of ocean that separate Pacific Island states from each other, and from the nearest continents, coupled with a lack of fossil-fuel reserves and (for Kiribati and some of its neighbours) arable land for subsistence agriculture, make long boat trips and extensive imports of food, fuel and other essential goods a fact of life. It does not help that the populations of Pacific Island states are highly dispersed, or that the fixtures of the region''s economic life — fishing boats — require a constant flow of gasoline.

All of that makes Pacific Island states especially vulnerable to swings in prices of essential commodities, particularly transportation and cooking fuel. A study by the Asian Development Bank found that, in 2006, fossil fuel — mainly oil — made up 85 per cent of the countries'' total energy mix. If the region''s most populous countries, Fiji and Papua New Guinea, were excluded from that calculation, the rate climbed to 99 per cent. By contrast, the average for the Asia-Pacific region was 45 per cent, and just 34 per cent globally.

The South Pacific''s energy dependence was painfully obvious during the global financial crisis of 2008, when a spike in oil and food prices led to inflation ranging from 2.5 per cent to 12 per cent, according to a recent study, in the journal Resources, by Matthew Dornan, a South Pacific expert at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. In 2009, Pacific island states spent a whopping US$873 million on fuel imports — about three-quarters of it for transportation. Amid the crisis, a group of Pacific energy ministers declared that their economies were "the most vulnerable in the world to rising oil prices."

“The big issue in the region is that government attention and funds have been directed towards the state-owned power utilities that provide electricity in urban areas.”Matthew Dornan, Australian National UniversityGeographic isolation clearly impedes construction of electricity grids and other energy infrastructure projects on all but the largest South Pacific islands. But Dornan said geography is not the only problem; he also blames the "very regressive" approach that many of the region''s governments take to energy development. "The big issue in the region is that government attention and funds have been directed towards the state-owned power utilities that provide electricity in urban areas," he said.

"They''ve been provided in such a way to keep electricity prices low for urban households, and that''s an understandable endeavor given the low incomes of many people in these countries," Dornan added. Yet urban-centric energy policies have also "placed those utilities in a difficult financial position and prevented them from extending their electricity networks. And it''s prevented them from expanding off-grid power supply in rural areas."

In 2014, Dornan wrote in the journal Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews that electrification rates in Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands were in the teens. By that measure, Kiribati, with a 63 per cent electrification rate, looked rather modern. Yet even that rate was less than Britain''s (66 per cent) on the eve of the Second World War.

Many South Pacific governments have turned to off-grid solar power in recent years as a way of reducing their energy dependence in remote areas while improving residents'' standard of living. The approach appears to make sense primarily because off-grid systems require far less investment and engineering than a traditional power grid would.

"It''s a problem of scale," said Anirudh Singh, a renewable-energy specialist at the University of the South Pacific (USP) in Fiji. "Grid electrification is not feasible; therefore [planners] have to largely resort to stand-alone systems" in rural areas. He added that the push for stand-alone systems began about two decades ago and has intensified as the cost of solar systems has steadily declined.

But infrastructure and geography are not the only motivating factors. According to Dornan, Pacific island states appear to like off-grid programs at least partly because they attract development assistance. Many of the region''s low-lying states also face an existential risk in the form of projected sea-level rises linked to climate change, and Dornan said the region''s leaders may see greening their energy sources as a means of strengthening their negotiating hands at international climate-change negotiations. (Kiribati''s former president, Anote Tong, who stepped down in early March, has been particularly outspoken on the risks that climate change poses to low-lying island nations.)

About Solar storage kiribati

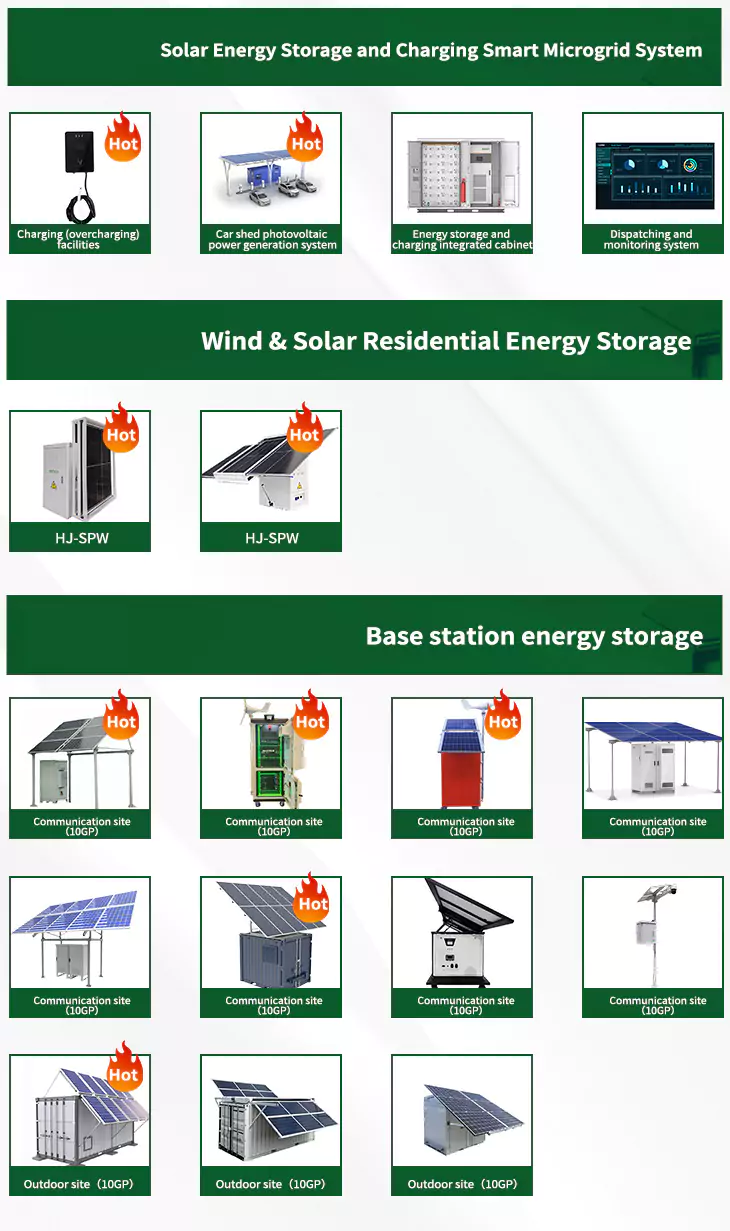

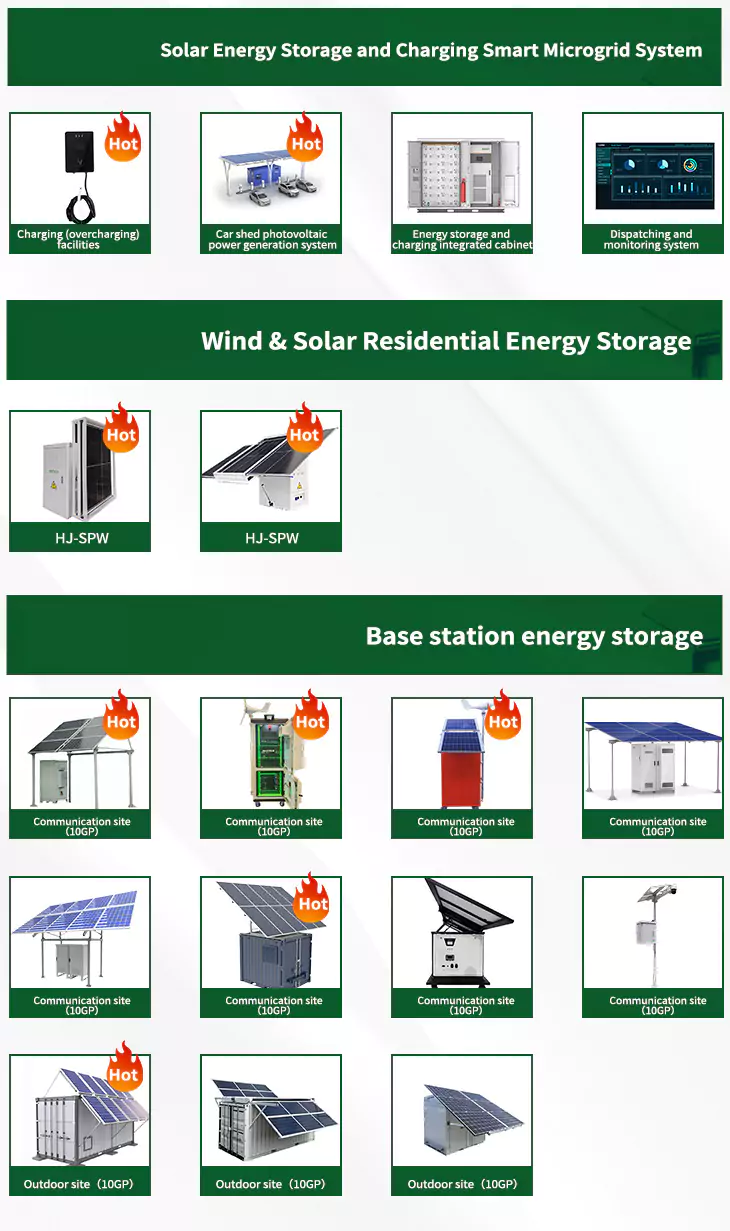

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in Solar storage kiribati have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient Solar storage kiribati for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various Solar storage kiribati featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents