Transition dynamics are highly context-sensitive and place-specific. Our theorization of transitions needs to be built upon such place-based specificities, as well as global interdependencies and dynamics between different geographical scales.

Colonial pasts often shape current investments in energy infrastructures, e.g., via knowledge production or developmental agendas, with influential roles played by donor agencies, development banks, and trans-national (state-owned) enterprises. This calls for a differentiated and historically informed analysis of the political economy of energy investments.

Furthermore, notions of energy justice and democracy relate to questions of the provision of basic needs, the relationship between energy transitions, energy crisis, and energy access, and what adverse effects of energy infrastructures particular groups reasonably have to accept. Often, notions of justice are intertwined with complex ideas of epistemic justice [34], for example, when individuals are excluded from decision-making. By empirically researching justice concerns and democratic aspirations of individuals, and by giving voice especially to ''silenced voices,'' researchers can contribute to articulating alternatives and support productive ways of dealing with conflicts.

These themes are further explored in the three "Introduction", "Understanding the specificity of interdependent, yet place-based transitions", "Engaging with history and the political economy of energy transitions" sections below. Based on that, we reflect on more plural understandings of societal change in "Appreciating plural notions of energy justice" sections; before we bring a final reflection on the genesis and outcome of this article collection in "Conclusion" sections.

In their contribution to this collection, Koepke et al. (2022), for example, show how "socio-technical heterogeneity contributes significantly to the functioning of Southern cities by responding to user demands that are unmet by conventional, centralized grids" e.g. when "socio-technical alternatives" in electricity services "serve low-income users, the middle classes, and urban elites".

In line with this heterogeneous reality of energy landscapes, Edomah''s (2022) paper in this article collection leans on various epochs to contextualize the energy transition and energy systems change in Nigeria: pre-industrial (1800); early industrial (1850); industrial (1900); late industrial (1950); and information (2000). Accordingly, '' from the preindustrial (agricultural) era the 1800s, we notice a gradual change in technology use and social practices that became more energy intensive, thus requiring more energy dense sources'' (Edomah, 2022).

Building on the case of deployment of digitalization technologies in Nigeria and South Africa, Nawaiwu (2022, this collection) explores the potential of digital technologies in energy transitions. The article sets up the following argument in favor of digital technologies:

"The use of digital technologies to enable sustainable energy transitions involves the adoption and implementation of these classes of technologies in ways that leverage their unique characteristics to offer new models of production, distribution, and consumption of energy."

In this context, among the promises of digital technologies is the possibility to move households away from the generation of energy, most often from fossil fuel sources, and to let them join platforms through which renewable energies can be implemented, for example, through the constitution of smart grids or the use of blockchain technology. The results show an apparent disconnect between the regulatory and policy environment in which such technologies are deployed, on one hand, and the localized efforts to implement them on the other. A similar concern informs the analysis of Gebresslassie et al. (2022, in this collection), in which regulatory environments are not always open to the adoption of challenging technologies, in this case, decentralized energy systems.

Their papers reflect on the heterogeneous co-construction of socio-technical relations in processes that simultaneously sediment material infrastructures and governance structures. This explains the stubborn persistence of the socio-technical systems that structure our life—what Hommels called obduracy [39]. Perhaps the next generation of research on transitions can also analyse how intentions of change, and the resulting changes, can be integrated within such systems in the forms of localized, experimental interventions.

Energy transitions are shaped by complex histories of colonial and imperial domination, which become highly visible in contexts where such histories are recent or even still present. Newell [40] has argued that energy transitions must engage with the racialized nature of energy systems, as manifested in the material constitution of infrastructures, the governance of energy systems, and their operation. The constitution of energy systems placed value on some lives over others, and transition efforts so far have done little to address the racialized constitution of energy systems [41].

For example, to the extent that energy transitions are connected to decreasing global GHG emissions, there is a danger that they become an arena for ''carbon colonialism.'' A common understanding of carbon colonialism relates to the concern that powerful countries (in the ''North'') invest and coerce other countries to occupy the ''discursive and physical spaces in the global South'' in the name of environmental and climate protection while also masking historical responsibilities in accounting for carbon emissions ([35]; p. 5). They say:

"Putting a price on and commodifying emission responsibilities means that historical injustices of extraction and colonization, which have led to inequalities of wealth between (as well as within) the global North and South, can continue in new forms" ([35]; p. 6)

Yet, it is not only a question of the reproduction of the imperial structures of colonialism across transnational spaces. Colonial histories are already inscribed in the spaces of transition and shape not only what practices are possible but also what futures are imaginable [32]. The articles in this collection demonstrate the complex interplay between global pressures on the energy transition and place-based dynamics.

For example, Koepke et al. (2022, in this collection) observed in Dar es Salaam that "development partners have promoted managerial modalities to reform African infrastructure sectors whose state-led, hierarchical organization was considered inefficient." Such past interventions seem to have contributed significantly to the infrastructural heterogeneity and to the institutional complexity seen today, which make it particularly difficult to orchestrate energy transitions. The tension between diversity in initiatives and the need to align those with evidence of the actual occurrence of a transition is visible in the analysis.

The quest for appreciating diversity is undoubtedly most important when understanding notions of justice, which can differ not only from one person to the next but also from one moment to the other.

Energy transitions are happening in a context of increasing attention to the distributional impacts of extensive infrastructure reconfigurations. While in the context of energy, a sustainability transition is linked to the remediation of energy access challenges, in practice, energy transitions will directly impact different population groups. Recent work has put notions of energy justice at the forefront [44]. Following scholarship on environmental justice, ideas of energy justice emphasize distributional aspects of socio-technical transitions, the recognition of a diverse set of needs and impacts, and the representation and participation of a wide range of stakeholders in the politics of energy.

While questions of justice are already integrated into transitions scholarship [45, 46], they are even more salient in transitions unfolding in the context of significant disparities of income and infrastructure access across the population and alongside complex energy access challenges. As Swilling argues, it is unlikely that the energy transition will be just [23] if it can happen at all:

"the expected just transition this could give rise to will not happen simply because there is a shared normative commitment, as is now reflected in the adoption of the SDGs [Sustainable Development Goals] and before that in the GED [Green Economy Discourse]. Nor will much progress be made by formulating bland managerial policy prescriptions that ignore underlying power dynamics and paradigm differences." ([47]; p. 667)

The complexity of such constellations cannot be overemphasized. Koepe et al. (2022, in this collection), for example, show how managers at Dar es Salaam''s integrated electricity utility TANESCO struggle to navigate across different modes of governance to accommodate "conflicting managerial interests and hierarchically set goals while justifying this practice as serving broader public interests."

In the context of digitalization in Nigeria and South Africa, Nwaiwu (2022, this collection) recovers the leapfrogging argument, demonstrating that digitalization offers a new leapfrogging promise:

"What can be learned from the current state of sustainable energy transitions in Nigeria and South Africa is that digital technologies offer the possibility of a more efficient way to leapfrog the infrastructure deficit required to address energy poverty in sub-Saharan Africa."

The challenge, as the paper explains, is that it is still too early to understand the distributional impacts of digital technologies, although they can facilitate small-scale electricity generation (mini-grids). Transparent billing (facilitated by blockchains) may simply curtail access to technology, further reinforcing distributive and procedural injustices.

Just transition'' claims relate not only to the need to examine the impacts of those transitions but also point toward the need to link transitions to broader drivers of structural oppression and exclusion that shape people''s lives. Intersectional approaches that seek to redress existing injustices are increasingly central to the energy transition, and the experiences from Africa are putting those approaches at the forefront.

About Energy independence mbabane

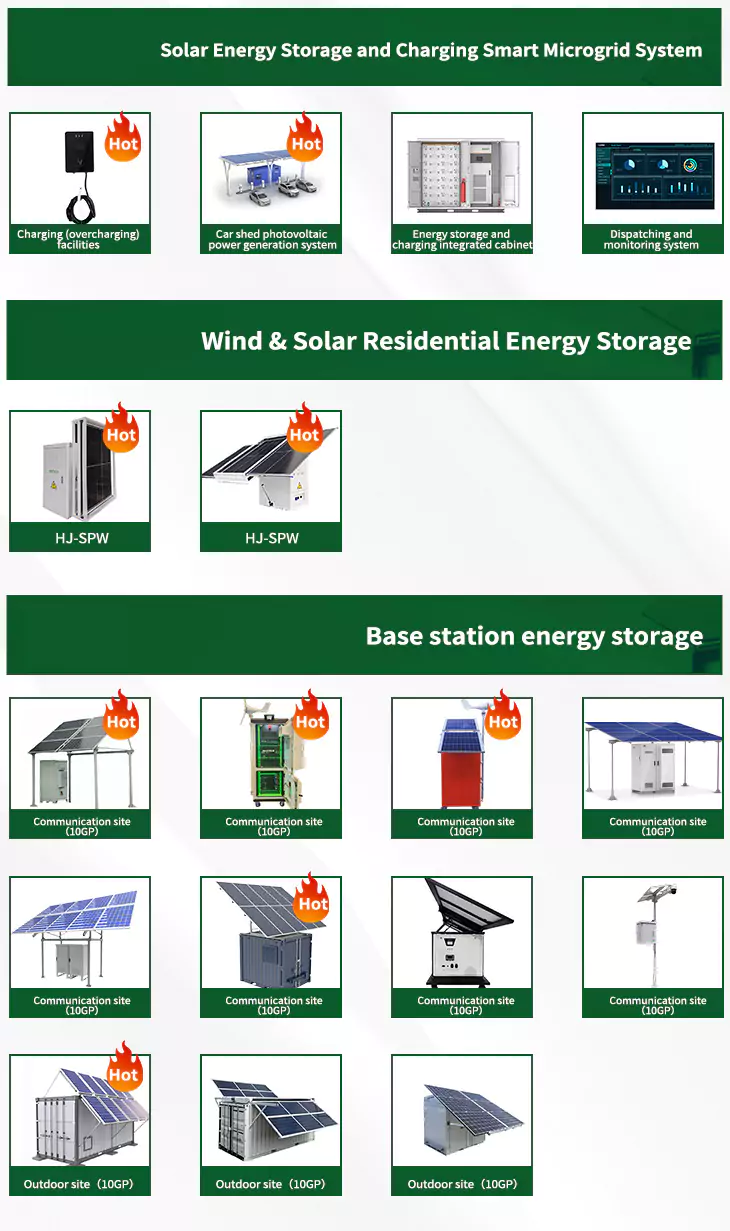

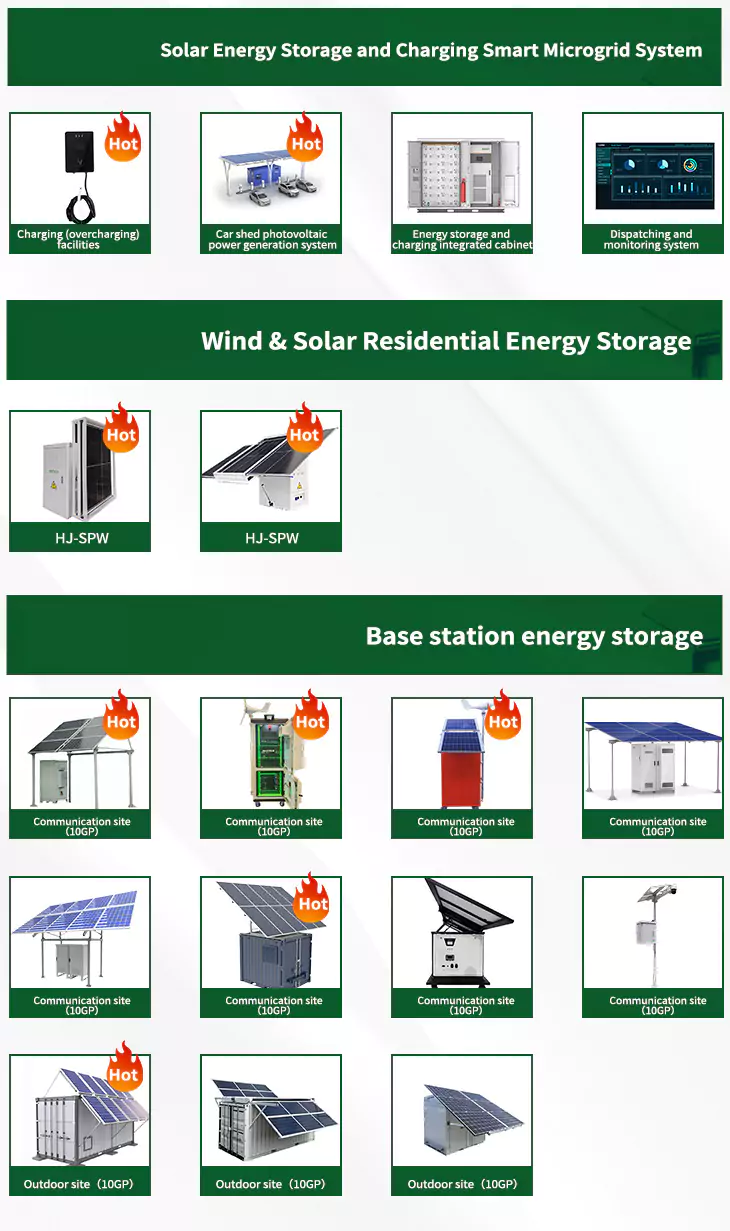

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in Energy independence mbabane have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient Energy independence mbabane for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various Energy independence mbabane featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents