More than half (53%) of New Zealand''s gross greenhouse gas emissions are from agriculture, mainly methane from sheep and cow belches.[6][7] Between 1990 and 2022, New Zealand''s gross emissions (excluding removals from land use and forestry) increased by 14%. When the uptake of carbon dioxide by forests (sequestration) is taken into account, net emissions (including carbon removals from land use and forestry) increased by 33% since 1990.[6]

Climate change is being responded to in a variety of ways by civil society and the New Zealand Government. This includes participation in international treaties and in social and political debates related to climate change. New Zealand has an emissions trading scheme, and in 2019 the government introduced the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Bill which created a Climate Change Commission responsible for advising government on policies and emissions budgets.[8][9]

New Zealand has a relatively unique emissions profile. In 2022, agriculture contributed 53% of total gross emissions; energy (including transport), 37%; industry, 6%; waste, 4%.[6] Based on the latest available Inventory data for 2022, New Zealand''s gross emissions per capita were above the average for developed countries.[6] In other Kyoto Protocol Annex 1 countries, agriculture typically contributes about 12% of total emissions.[13]

Between 1990 and 2022, New Zealand emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) increased by 24%; methane (CH4) by 2%; and nitrous oxide (N2O) by 35%. The total of all combined fluorinated gases have increased by 87%.[6]

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme, which came into effect in 2010, was intended to provide a mechanism which encouraged different sectors of the economy to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. It may have slowed the increase somewhat. Between 2007 and 2017 total national emissions decreased 0.9%, reflecting growth in renewable energy generation.[14] However, between 2016 and 2017, New Zealand''s gross emissions jumped 2.2%, bringing the total (or gross) increase in greenhouse gas emissions between 1990 and 2017 to 23.1%.[15]

In 2018, on a per capita basis, New Zealand was the 21st biggest contributor to global emissions in the world and fifth highest in the OECD.[16]

Modelled wind directions indicated that air flows were originating from 55 degrees south. The Baring Head data shows about the same overall rate of increase in CO2 as the measurements from the Mauna Loa Observatory, but with a smaller seasonal variation. The rate of increase in 2005 was 2.5 parts per million per year.[21] The Baring Head record is the longest continuous record of atmospheric CO2 in the Southern Hemisphere and it featured in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007 in conjunction with the better-known Mauna Loa record.[22]

According to estimates from the International Energy Association, New Zealand''s per capita carbon dioxide emissions roughly doubled from 1970 to 2000 and then exceeded the per capita carbon dioxide emissions of either the United Kingdom or the European Union.[23] Per capita carbon dioxide emissions are in the highest quartile of global emissions.[24]

In 2003, the Government proposed an Agricultural emissions research levy to fund research into reducing ruminant emissions. The proposal, popularly called a "fart tax", was strongly opposed by Federated Farmers[30] and was later abandoned.[31]

The Livestock Emissions and Abatement Research Network (LEARN) was launched in 2007 to address livestock emissions.[32] The Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium between the New Zealand government and industry groups seeks to reduce agricultural emissions through the funding of research.At the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, the New Zealand government announced the formation of the Global Research Alliance involving 20 other countries. New Zealand will contribute NZ$45 million over four years towards research on agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.[33]

In 2019, it was announced that the government had awarded funding to cultivate and research a red native seaweed known as Asparagopsis armata to the Cawthron Institute in Nelson. This particular seaweed has been found to reduce methane emissions from animals by as much as 80% when small amounts (2%) are added as a supplement to animal food.[34]

Nitrous oxide is emitted primarily from agriculture, but also comes from industrial processes and fossil fuel combustion. Over 100 years, it is 298 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat. In New Zealand in 2018, 92.5% of N2O came from agricultural soils mainly due to urine and dung deposited by grazing animals. Overall, N2O emissions increased 54% from 1990 to 2018 and now make up 19% of all agricultural emissions.[35]

The agriculture industry is responsible for half of all emissions in New Zealand, but contributes less than 7% of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the last ten years[when?] there have been modest reductions in emissions from sheep, beef, deer and poultry farms, but these have been offset by a rapid growth in dairy farming which has had the biggest increase in emissions of any single industry. In fact, emissions from dairy have risen 27% over the decade such that this industry is now responsible for more emissions than the manufacturing and electricity and gas supply industries combined.[36]

Dairy giant Fonterra is responsible for 20% of New Zealand''s entire greenhouse gas emissions.[37] This is largely due to Fonterra''s use of coal-powered boilers to dry milk into milk powder. Clean energy expert, Michael Liebreich, describes the use of coal for this process as "insane". Genesis Energy Limited chief executive, Marc England, said in 2019 that Fonterra is using more coal than Genesis uses at its Huntly power station and should use electricity, which is already 85% renewable, in its milk powder factories.[38]

Both historically and presently, the majority of New Zealand''s electricity has been generated from hydroelectricity. In the 2019 calendar year, 82.4% of the country''s electricity was generated from renewable or low-carbon resources: 58.2% from hydroelectricity, 17.4% from geothermal, 12.6% from natural gas, 5.1% from wind, 4.9% from coal, and 1.7% from other sources.[39]

A major barrier in decommissioning Huntly is ensuring continued security of supply, especially to Auckland and Northland. In June 2019, transmission grid operator Transpower analysed the effects of closing the two remaining coal-fired units at Huntly on its grid. It concluded that without the coal-fired units and no major new generation or transmission upgrades, voltage collapse could occur during Auckland and Northland winter peak demand from 2023 onwards with the 400 MW combined-cycle gas turbine Huntly Unit 5 out of service, or from 2019 onwards with both Huntly Unit 5 and any one of the 220,000-volt transmission lines from Whakamaru out of service.[43]

The ten companies which emit the most greenhouse gases in New Zealand are Fonterra, Z Energy, Air New Zealand, Methanex, Marsden Point Oil Refinery, BP, Exxon Mobil, Genesis Energy Limited, Contact Energy, and Fletcher Building. These companies emit around 54.5 million tonnes of CO2 each year – more than two thirds of New Zealand''s total emissions.[44]

The bulk of household emissions stem from New Zealanders'' reliance on combustion engine cars for transport, with relatively small amounts coming from heating and cooling.[36] In 2019, there were less than 10,000 electric vehicles on New Zealand roads leading the New Zealand Productivity Commission to recommend a rapid and comprehensive switch from petrol cars to EVs. Professor David Frame, director of Victoria University''s New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute says "the growth (in use) of electric cars has been nowhere fast enough to get to where we''ve said we want to be by 2030".[45]

In the last ten years,[when?] New Zealand and Australia were among a handful of developed nations where household emissions are increasing. The others are all Eastern European countries.[36] A New Zealand study conducted in 2019 says housing must shrink its carbon footprint by 80% to meet New Zealand''s commitment to the Paris Agreement - adding that a typical new Kiwi home emits five times as much carbon dioxide as it should if the world is to stay below 2C warming.[46]

One reason for this is that New Zealand is one of only three countries without fleet-wide vehicle emissions standards[50] leading the New Zealand Productivity Commission to argue the country is "becoming a dumping ground for high-emitting cars from other nations busy decarbonising their highways".[45] As a result, there has been little incentive for the public to buy electric cars or hybrids; as at May 2019, only 61,000 hybrid vehicles were registered in New Zealand.[51][needs update]

However, in July 2019, Associate Transport Minister Julie Anne Genter announced a government proposal to impose substantial price discounts on imported cars with low emissions and price penalties on those with high emissions. This would knock about $8,000 off the price of new or near-new imported electric vehicles (EVs) while the heaviest petrol using polluters would cost $3,000 more. The scheme is expected to remove more than five million tonnes of CO2 from New Zealand''s emissions even though it only applies to (new and used) vehicles coming into the country and does not apply to the 3.2 million vehicles already on the roads which account for 74% of annual sales.[52][53]

Around 589 km (366 mi) of New Zealand''s 4,128 km (2,565 mi) of railway track is electrified. This includes the majority of the Auckland and Wellington regional commuter networks (with the notable exception of Papakura to Pukekohe and Wellington to Masterton services), and the central section of the North Island Main Trunk between Hamilton and Palmerston North. There is no electrified track in the South Island.

New Zealand''s aviation emissions have resumed increasing rapidly after a decline in 2020 caused by the COVID19 pandemic. From 1990 to 2019 New Zealand''s aviation emissions increased by 116% to 4.9 Mt CO2. New Zealand ranks 4th highest in the world for per-capita domestic aviation emissions and 6th highest in the world for per-capita international aviation emissions, which are about 10 times the world average. From 2015 to 2019 international aviation emissions rose more rapidly at more than 40%. In summary,New Zealand has particularly high aviation emissions and has been on a very rapid growth path that is incompatible with the Paris Agreement on climate change.[54]

Air New Zealand is one of the country''s largest climate polluters, emitting more than 3.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. This represents about 4% of New Zealand''s total greenhouse gas emissions. Air New Zealand offers a voluntary scheme, called FlyNeutral, which allows passengers buy carbon credits to offset their flights. Currently customers offset less than 1.5% of the airline''s total carbon emissions. Air New Zealand also offsets its domestic emissions through the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme. The airline says that in 2019 it will purchase emission units to cover 100% of its domestic carbon footprint.[55]

New Zealand has reliable air temperature records going back to the early 1900s. Temperatures are taken from seven climate stations throughout the country and combined into an average.

New Zealand''s largest glacier, the Tasman Glacier, has retreated about 180 metres a year on average since the 1990s and the glacier''s terminal lake, Tasman Lake, is expanding at the expense of the glacier. Massey University scientists expect that Lake Tasman will stabilise at a maximum size in about 10 to 19 years, and eventually the Tasman Glacier will disappear completely. In 1973 the Tasman Glacier had no terminal lake and by 2008 Tasman Lake was 7 km long, 2 km wide and 245 m deep.[70] Between 1990 and 2015, Tasman Glacier retreated 4.5 kilometres (2.8 miles), mostly from calving.[71]

About New zealand climate change

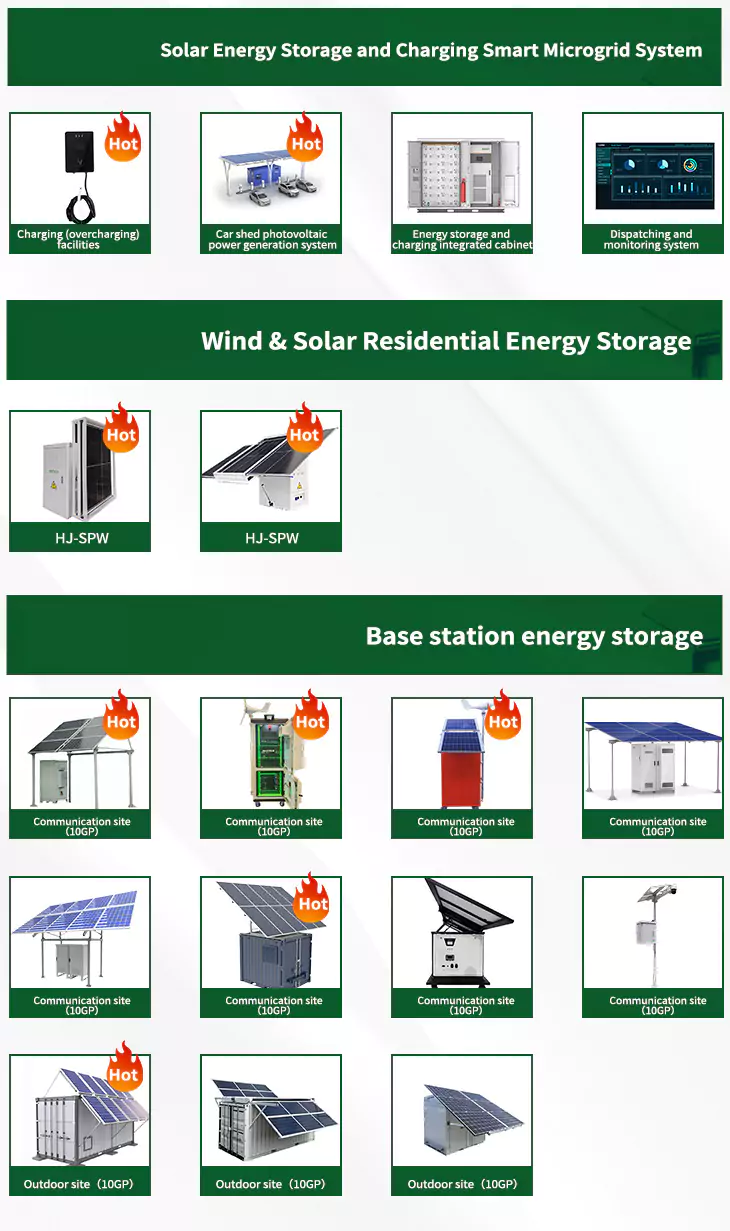

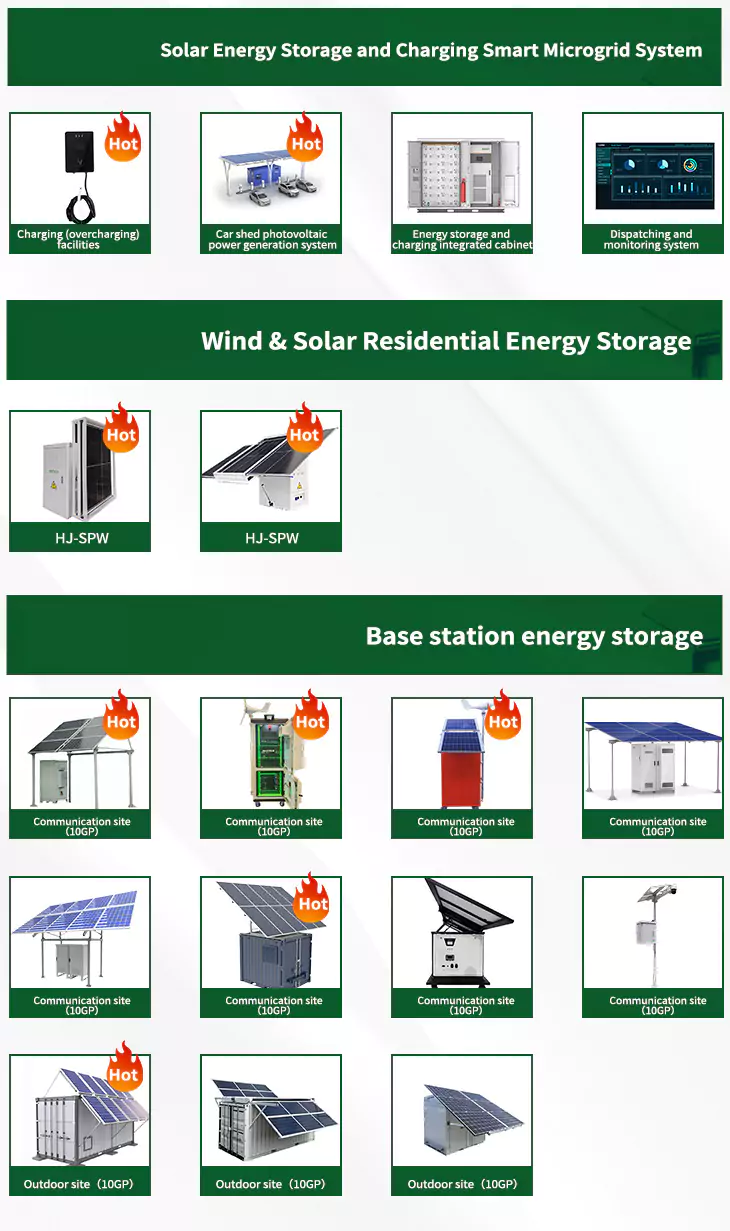

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in New zealand climate change have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient New zealand climate change for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various New zealand climate change featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents